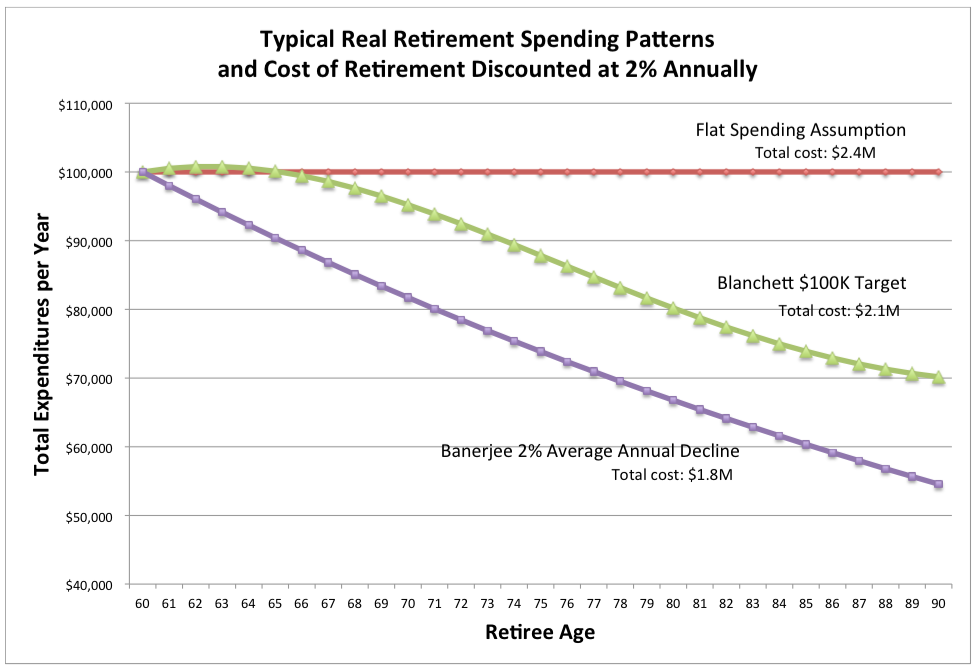

The amount that we can safely spend from retirement savings in the current year depends heavily on the assumptions we make about future spending trends. If our future spending needs will decline, spending rules that assume constant real spending will be unnecessarily conservative and, of course, if future spending will increase, those spending rules will recommend spending that may not be sustainable.

What assumptions should our retirement plan make about future spending? The two papers I reference offer some clues.

First, Banerjee reports that spending in retirement increased for only 16% of the households in the data he studied, while it declined for 66% of them. It is significantly more likely that your expenditures will decline as you age, but they might not, so our retirement plans should also consider worst case outcomes.

We could assume a worst case, that expenditures will increase perhaps 1% per year on average, but that would significantly increase the predicted cost of retirement. If we assume we will live 30 years or more, that our market returns will be quite conservative by historical standards and that our expenses will grow in retirement, we will quickly realize that hardly anyone could afford that retirement. Making lots of conservative assumptions doesn't make a very good plan.

Blanchett offers additional insights by segmenting the data based on the level of annual spending relative to net worth. He creates four categories of consumption: low spenders with high net worth, low spenders with low net worth, high spenders with high net worth and high spenders with low net worth. By figuring out into which group you best fit, you may be able to narrow the field of spending assumptions for your plan.

The dividing line for high and low spenders was $30,000 per year and the hurdle for high net worth was $400,000 in Blanchett's study. These are the median values for his data sample, not for the population of retirees. In other words, more than $30,000 of annual spending made households in the data sample high spenders relative to other households in the sample, but that amount wouldn't make you a high spender relative to all other retirees in the U.S. today. The breakpoints for the larger population of retirees would likely be much higher. Blanchett is showing that expenditures in retirement depend on the relationship between annual spending and net worth; he is not claiming that these are the dividing lines for all retirees.

Blanchett notes that two of these groups, Low Spending, Low Net Worth and High Spending, High Net Worth retirees, consume efficiently (green), while the other two groups consume too much (red) or too little (yellow).

Following is a diagram from Blanchett's paper plotting these four segments. Please note the very important point, as I explained in Spending Typically Declines as We Age, that these graphs show annual rate of change in spending and not annual spending, itself. With the exception of Low Spending, High Net Worth households (the red squares on Panel B) almost all of the annual changes in expenditures are negative, meaning spending declines throughout retirement for the other three groups. (Double-click the chart for a larger image.)

Notice that the following graphs of annual spending are quite different than Blanchett's graphs of annual spending change above. Because some readers have mistaken the Blanchett "smile" rate-of-annual-change graphs for annual expenditures graphs, I provide both in the examples below.

In fact, Blanchett's paper shows this in his Figure 7, though most of that paper addresses annual spending change and not annual real dollar spending. My graphs will show typical real dollar annual spending that is derived from the rate-of-change graph to its right. I place the spending function on the left because I believe that information will be more meaningful to most of my readers, and I switched Panels A and B in Blanchett's Figure 7 for consistency – the charts on the left always show annual spending.

Let me be very clear about this. The Blanchett smile curves, like Panel A above, show how quickly typical spending changes each year. The spending curves, like Panel B above, show how much spending changes in real dollars and, in most cases, spending goes steadily downward throughout retirement, like the curves in Panel B.

Now, let's look at Blanchett's four spending/net worth classifications.

Low Spending, Low Net Worth households likely spend a large portion of their budget on non-discretionary expenses with little opportunity for reducing expenses later in retirement. We usually give up some discretionary items later in retirement, like extensive travel and sports, and these households have fewer of those to eliminate, so expenditures don't decline a lot with age.

High Spending, High Net Worth households also consume efficiently and will likely see greater declines in spending than Low Spending, Low Net Worth households, because they will have more discretionary spending to eliminate as they age.

Low Spending, High Net Worth households appear to have the highest probability of increased expenditures throughout retirement, but they can afford it. They are underspending. A likely cause for such an increase in expenditures, in fact, is recognition over time that they have the resources to spend more.

This graph also demonstrates the key point that increasing expenditures don't necessarily mean that retirement is getting more expensive and decreasing expenditures don't mean it is getting less expensive. They mean that retirees are spending more or less. Expenditures, the subject of this analysis, are not the same as expenses. Sometimes expenditures change because retirees have to spend less and sometimes it is because they can spend more.

High Spending, Low Net Worth households also consume inefficiently and they are likely to recognize as they age that their level of spending is unsustainable. This realization will eventually lead to declining expenditures later in retirement, as can be seen in the following chart.

The next chart combines all four annual spending curves for comparison. The two curves in the middle result from efficient consumption. Inefficient consumption produces the two extremes.

Your personal ratio of annual spending to net worth should suggest whether your own spending is more likely to rise, fall, or remain somewhat constant throughout retirement.

To summarize this information, Banerjee tells us that two-thirds of retirees will experience declining expenditures as they age and only 16% will see increased spending. Blanchett tells us that spending will likely increase for Low Spending, High Net Worth households as they realize they are able to spend more as they age, as it will likely decrease for High Spending, Low Net Worth households as they realize they are running out of savings. Among households that consume efficiently, those with High Spending and High Net Worth are more likely to spend less later in retirement because they will have more discretionary expenses to "age out of" than will Low Spending, Low Net Worth households.

Some expenditures change for reasons that have little to do with how much annual spending a retiree targets or how wealthy they are. Some changes are the result of aging. Health care expenses tend to increase as we get older but we also become less active and other expenses decline. I recently read that international air travel declines among septuagenarians and domestic air travel declines among octogenarians. I suspect the sales of bungee-jumping and rock-climbing gear decline in those market segments, as well. I spend less on hair care expenses.

These two studies deal with typical retiree spending patterns and assume that expenditures will follow some trend, rising, constant or declining, throughout retirement. They don't, however, deal with the most likely scenario for an individual household, irregular net spending.

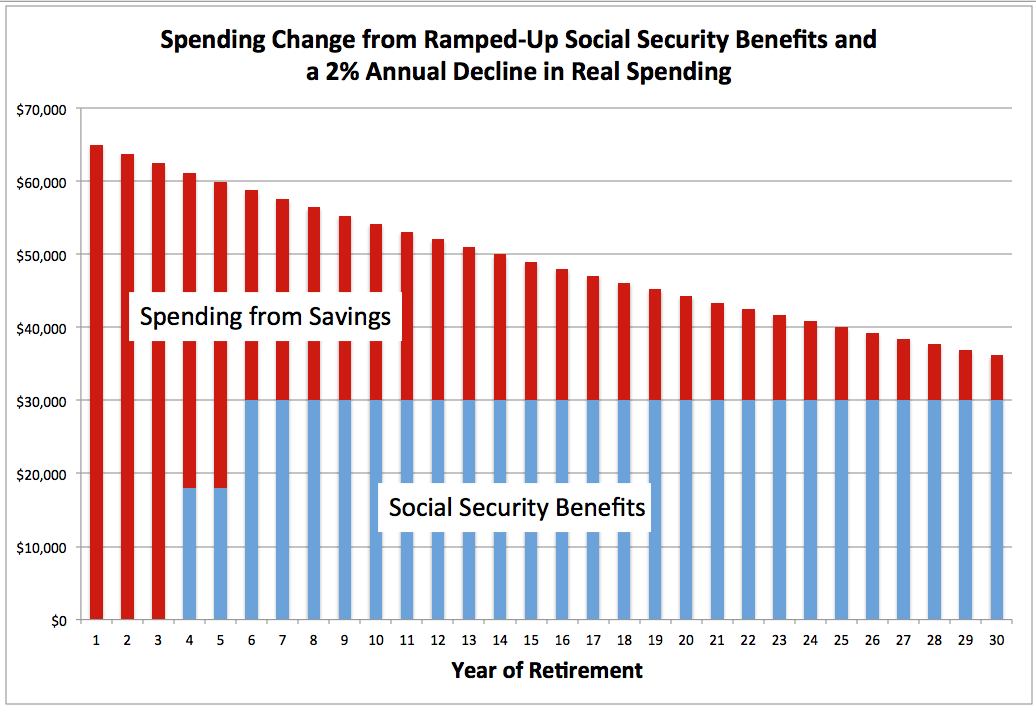

Both income and expenses in retirement are likely to vary significantly over time. Income will vary, for instance, as Social Security benefits ramp up for retired couples and more income needs to be withdrawn from savings early in retirement. There may also be large planned expenses later in retirement, like college for a child or grandchild. Net spending is the important consideration, the difference between annual income and annual expenses. Irregular net spending from savings might look like the red bars in the following chart:

These irregular net spending years, whether they are caused by changing income or changing expenses, must be considered when calculating a sustainable amount to spend in the current year. Like steadily rising or steadily declining expenditures, spending rules assume flat future spending and don't accommodate irregular net spending very well.

It is helpful to know that expenses typically decline in real terms throughout retirement, but yours may not. You need to plan for expected spending declines but be prepared for a worse case. Like portfolio returns, total expenditures in retirement are unpredictable.

So, most retirement income strategies assume constant spending throughout retirement and most retirement expenditure studies show that constant spending isn't the norm. What's a retiree supposed to do with that?

In my next post, Spending Rules That Fit the Patterns of Retirement, and Some That Don't, I'll explore spending strategies in light of future spending expectations.