In my last post, Are Social Security Benefits a Bond?,

I pointed out that many retirees might not be willing to implement a

very risky upside portfolio simply because they have an income floor to

rely on. Floor-Leverage Rule goes the 100%-equity bet one better.

Three, actually.

The Scott-Watson Floor-Leverage Rule and Zvi Bodie's floor-and-upside strategy are two very different variations of the Floor-and-Upside retirement income

strategy. These variations recommend different floor

allocations. The basic floor-and-upside strategy, described in

Risk Less and Prosper: Your Guide to Safer Investing by Zvi Bodie and Rachelle Taqqu, calls for the floor to at least

cover non-discretionary expenses.

Floor-Leverage Rule takes a different approach, recommending 85% of

all assets be included in the floor portfolio without regard to which expenses that might cover.

More to the point, the strategies also recommend varying

allocations for the upside portfolio. I envision a reasonable, 50%

equity portfolio, but Bodie, for example, recommends that the upside

portfolio consist of 90% Treasury bonds and 10% long-term call options (LEAPs). (Nassem Taleb has also suggested this strategy.) Scott and Watson go even farther, recommending a 200%-leveraged (3x) stock

indexed ETF. One such fund, ProShares Ultra S&P500 (SSO), which is

“only” leveraged 100%, fell 79% in the last bear market. I can’t find a

3x leveraged fund that was around back then.

You

can implement the upside portfolio with any amount of risk you want.

Yours will still be a floor-and-upside strategy if you implement the

upside portfolio with something other than Bodie's or Scott's approach.

Why do

these experts, some of the most highly-regarded in the retirement

planning field, recommend such risky upside portfolios and are they a

good idea?

I think these recommendations are made with

the assumption that retirees with a sound floor of income will be

willing to take huge risks with their upside portfolio, but I am not,

and I doubt that many retirees are. I think this may be another case of

the pig having a different perspective than the chicken.

They

also assume that retirees value floor assets

and upside assets equally, in other words, that losing their entire

upside portfolio would be OK if they had an adequate floor. Floor assets

and the upside portfolio are both wealth, but the upside portfolio has

something that the floor assets don’t and that retirees find quite

attractive — hope.

Recommendations for highly-leveraged

and risky upside portfolios appear to assume that a retiree will always

value guaranteed income at least as highly as they value having an

upside portfolio. In other words, were they to lose most or all of their

upside portfolio (a 3x leveraged portfolio is wiped out by a 33% drop

in stock prices), retirees wouldn’t be overly concerned because they

would still have Social Security benefits and annuities to meet their

needs. But, they would also have lost their upside potential. That

wouldn’t make me happy.

While I can’t produce

studies

that show retirees would prefer not to make a huge, risky bet with their

upside portfolios, I believe we can infer that from other behavior. The

evidence seems clear that retirees are generally reluctant to annuitize

their entire savings at retirement, and many advisers recommend against

that, as well. I believe the reasons are reluctance to give up the

opportunity for improving their standard of living in a bull market

(hope) and

hesitance to give up all liquidity, among others. If an unforeseen

expense comes along, you can't withdraw extra cash from Social Security

benefits or an annuity.

If

we know that retirees are reluctant to create a retirement income

strategy that consists of all annuities (private or Social Security),

then we should assume that they would be reluctant to risk backing into that position by losing most or all of

their upside portfolio and being left with illiquid annuities. It would

follow, then, that they would not be willing to make huge, risky bets

with their entire upside portfolio. Although Bodie’s call options

strategy makes risky bets, it does so with only 10% of the portfolio. The

Floor-Leverage Rule risks losing all or most of the upside portfolio

and, with it, any chance of a higher standard of living.

In Three Portfolios, I showed

that considering Social Security benefits a bond forces most

retirees into a much riskier upside portfolio, often 100% stocks. Many

argue that a 100%-equity upside portfolio would be acceptable because

the retiree has a floor to rely on, but that again assumes that a

retiree values floor assets at least as highly as upside potential. I

argue that at the margin, this isn’t typically the case.

Retirees may

value floor assets quite highly at the beginning, but at some point they

will value upside potential and liquidity more than they value more

floor assets. In other words, they won’t want to fully annuitize their

savings and give up the opportunity to improve their lot.

If

you truly don't mind that your upside portfolio might take wild swings

or it won't bother you when your call options expire worthless because

you would be content with your floor, then these might be reasonable

strategies for you. If you don't have an iron stomach, then investing

100% of your upside portfolio, let alone 300%, might not be the answer.

I'm

not suggesting that these are inappropriate strategies for everyone;

one might be a perfect fit for you. I'm pointing out that any strategy

that puts your upside portfolio at high risk assumes that you would be

fine with losing most or all of it, along with any opportunity you might

have for improving your standard of living with stock market gains,

because you have an income floor.

Are you?

A Floor-and a Lottery-Ticket strategy probably sounds better to chickens that it does to us pigs.

Friday, November 21, 2014

Hope and Your Retirement Portfolio

Three, actually.

The Scott-Watson Floor-Leverage Rule and Zvi Bodie's floor-and-upside strategy are two very different variations of the Floor-and-Upside retirement income strategy. These variations recommend different floor allocations. The basic floor-and-upside strategy, described in Risk Less and Prosper: Your Guide to Safer Investing by Zvi Bodie and Rachelle Taqqu, calls for the floor to at least cover non-discretionary expenses.

Floor-Leverage Rule takes a different approach, recommending 85% of all assets be included in the floor portfolio without regard to which expenses that might cover.

More to the point, the strategies also recommend varying allocations for the upside portfolio. I envision a reasonable, 50% equity portfolio, but Bodie, for example, recommends that the upside portfolio consist of 90% Treasury bonds and 10% long-term call options (LEAPs). (Nassem Taleb has also suggested this strategy.) Scott and Watson go even farther, recommending a 200%-leveraged (3x) stock indexed ETF. One such fund, ProShares Ultra S&P500 (SSO), which is “only” leveraged 100%, fell 79% in the last bear market. I can’t find a 3x leveraged fund that was around back then.

You can implement the upside portfolio with any amount of risk you want. Yours will still be a floor-and-upside strategy if you implement the upside portfolio with something other than Bodie's or Scott's approach.

Why do these experts, some of the most highly-regarded in the retirement planning field, recommend such risky upside portfolios and are they a good idea?

I think these recommendations are made with the assumption that retirees with a sound floor of income will be willing to take huge risks with their upside portfolio, but I am not, and I doubt that many retirees are. I think this may be another case of the pig having a different perspective than the chicken.

They also assume that retirees value floor assets and upside assets equally, in other words, that losing their entire upside portfolio would be OK if they had an adequate floor. Floor assets and the upside portfolio are both wealth, but the upside portfolio has something that the floor assets don’t and that retirees find quite attractive — hope.

Recommendations for highly-leveraged and risky upside portfolios appear to assume that a retiree will always value guaranteed income at least as highly as they value having an upside portfolio. In other words, were they to lose most or all of their upside portfolio (a 3x leveraged portfolio is wiped out by a 33% drop in stock prices), retirees wouldn’t be overly concerned because they would still have Social Security benefits and annuities to meet their needs. But, they would also have lost their upside potential. That wouldn’t make me happy.

While I can’t produce studies that show retirees would prefer not to make a huge, risky bet with their upside portfolios, I believe we can infer that from other behavior. The evidence seems clear that retirees are generally reluctant to annuitize their entire savings at retirement, and many advisers recommend against that, as well. I believe the reasons are reluctance to give up the opportunity for improving their standard of living in a bull market (hope) and hesitance to give up all liquidity, among others. If an unforeseen expense comes along, you can't withdraw extra cash from Social Security benefits or an annuity.

If we know that retirees are reluctant to create a retirement income strategy that consists of all annuities (private or Social Security), then we should assume that they would be reluctant to risk backing into that position by losing most or all of their upside portfolio and being left with illiquid annuities. It would follow, then, that they would not be willing to make huge, risky bets with their entire upside portfolio. Although Bodie’s call options strategy makes risky bets, it does so with only 10% of the portfolio. The Floor-Leverage Rule risks losing all or most of the upside portfolio and, with it, any chance of a higher standard of living.

In Three Portfolios, I showed that considering Social Security benefits a bond forces most retirees into a much riskier upside portfolio, often 100% stocks. Many argue that a 100%-equity upside portfolio would be acceptable because the retiree has a floor to rely on, but that again assumes that a retiree values floor assets at least as highly as upside potential. I argue that at the margin, this isn’t typically the case.

Retirees may value floor assets quite highly at the beginning, but at some point they will value upside potential and liquidity more than they value more floor assets. In other words, they won’t want to fully annuitize their savings and give up the opportunity to improve their lot.

If you truly don't mind that your upside portfolio might take wild swings or it won't bother you when your call options expire worthless because you would be content with your floor, then these might be reasonable strategies for you. If you don't have an iron stomach, then investing 100% of your upside portfolio, let alone 300%, might not be the answer.

I'm not suggesting that these are inappropriate strategies for everyone; one might be a perfect fit for you. I'm pointing out that any strategy that puts your upside portfolio at high risk assumes that you would be fine with losing most or all of it, along with any opportunity you might have for improving your standard of living with stock market gains, because you have an income floor.

Are you?

A Floor-and a Lottery-Ticket strategy probably sounds better to chickens that it does to us pigs.

Sunday, November 16, 2014

The Household Balance Sheet

The household balance sheet is one of many topics I've never quite gotten around to, but New Jersey retirement planner Michael Lonier recently offered to write a guest post and he has provided an outstanding introduction to the topic. Please check out Mike's impressive bio, too.

Enjoy!

Finding the Upside on

the Household Balance Sheet

Inescapably the time comes to consider that spending from

savings is different from saving from income. You survey your savings and

investments, scattered across a number of accounts, and the question arises,

how best to manage this money to get the best lifetime outcome for the

household when you are no longer earning a high income from full-time

employment?

Maybe you’re thinking about rolling over 20 or 30 years of

401(k) contributions made to an assortment of funds almost randomly picked over

the years, or are holding mostly cash after exiting the market during the 2008

crisis and now realize your money needs to work harder.

How do you organize—allocate—your savings and investments? How

much should you invest in stocks and bonds and keep in cash? How do you decide

what is best for you?

The Answer to the

Puzzle is More Puzzles

You can go with rules of the thumb, like the old chestnut “age

in bonds,” possibly with +/- some number adding a veneer of math to what is essentially

an arbitrary amount. You can put your money in a target date fund and pay a

fund company .20% to 1.00% to use their proprietary “glide path,” which adds a

costly layer of research to the age in bonds formula. (Hint: Index TDFs are

cheaper.) Dig deep enough, and your head might spin over how highly researched

glide paths can be so different.

You can ask an investment advisor who will give you a short

quiz and categorize you as conservative, moderately conservative, moderate,

moderately aggressive, or aggressive, and plug you into a model portfolio that

has somehow been matched with these categories which have somehow been matched

to the quiz answers you gave. If that doesn’t seem right, there are advisors who

will give you a longer quiz, or more categories, like south-by-south-west, or

both. And whichever direction you turn, you’ll pay maybe 1.00% a year.

Everyone has an answer to your puzzle. It’s just that

they’re different answers.

If you want to figure it out yourself, you are encouraged by

most experts to think deeply about your risk tolerance, how you are likely to react

when the bottom falls out, how much you can afford to lose (none!), and then

pick a number between 0% and 100% for stocks based on…your best guess.

Look Beyond Your

Investments to Your Balance Sheet

Your savings and investments are just one part of the

puzzle, one part of the resources you need to manage to get the best outcome.

You need to start at a place that accounts for all of your resources, that

balances what you have and what you need, revealing the weaknesses—the risk exposures—you

need to overcome. Financially, the place to start is with your household

balance sheet.

You are probably familiar with a simple net worth statement

that sums up current financial assets and debts and provides a snapshot of solvency.

A full household balance sheet for planning goes further than that. The asset

side of the balance sheet includes the current value of savings and investments

(financial capital), the discounted present value of expected future earnings

(human capital), and the discounted present value of expected Social Security

benefits and pensions (social capital). The liability side includes the

discounted present value of all expected future expenses, including debt

service and payoffs.

I won’t cover the details of how to calculate these present

values in this post, but though it sounds intensely complicated, it’s not. It’s

within the reach of anyone familiar with using Excel, and is no more involved

than examining your conscious for risk and divining an asset allocation from an

arbitrary formula. More importantly, it represents your specific household

situation in a logical and mathematical fashion without making any leaps of

faith about theoretical risk, personal inclinations, or market behavior. More

math, less magic.

Let’s look at a household balance sheet constructed in this

way (below). What does it tell us?

The assets on the left include $1,824,700 of financial

capital (FC), which is the current value of the household savings and

investments in retirement and taxable accounts. The relatively low $274,800 of

human capital (HC) suggests in this instance a household nearing retirement

with just a couple years of earnings remaining. Someone with ten or fifteen

years of employment ahead of them might have human capital over a million

dollars. Not surprisingly, the $1,977,000 present value of social capital

(SC)—Social Security and pension benefits over a 30-year retirement plan—is the

most valuable asset on this particular household balance sheet.

On the liability side, the present value of all expected

future expenses over the life if the plan (about 33 years in this case) is

shown as $3,381,400. Subtracting liabilities from assets, the balance sheet

shows a cushion or surplus of $695,200.

The financial lifecycle is the process of converting human

capital into a stream of income that covers ongoing current expenses while

building FC and SC to cover future expenses when HC has been “spent down” going

into retirement. The balance sheet shows the current relationships between

savings and investments, expected future earnings, accrued social capital

benefits, and expected future expenses, all either in current or discounted to

current dollars. It is the definitive household financial lifecycle scorecard,

and so is enormously useful in answering the question about how best to

allocate household resources.

Some simple math allows us to focus on the puzzle of

puzzles, the allocation of financial capital (below).

If we subtract the sum of HC and SC ($2,251,900) from

liabilities ($3,381,400), we are left with $1,129,400, the amount of expenses

that must be covered from savings and investments (from FC). We can call this

amount ($1,129,400) the income floor, the minimum amount of FC needed to cover

expected expenses. Note that the cushion of $695,200 from the balance sheet is

the amount of FC above the floor (FC of 1,824,700 minus floor of 1,129,400 = 695,200

cushion). This represents, after holding back some amount for reserves, the

risk capacity indicated by the balance sheet, or more simply, the upside. In

this case, after holding back a reserve of $125,100 from the cushion of $695,200,

the resulting upside is $570,100.

The final step is to lay this out as an allocation of

financial capital, based solely on the strength of the household balance sheet

(below).

Using the amounts above, the balance sheet shows an Upside/Floor/Longevity/Reserves allocation of 31.2%/61.9%/0%/6.9% (Longevity is a discussion for another day, but it generally starts with funding the deferral of SS benefits as the best deal around). Note that although this shows how much of FC can be exposed to upside risk and how much should be managed as floor, it is agnostic about how that should be done. In fact, as shown above under the “Adjusted” allocation, once you know what your balance sheet says, you can make an informed decision to expose more floor or less upside to risk, as you determine works best for you. In this case, about 9% of the floor has been allocated to upside (increasing the balance sheet upside allocation from 31.2% to an adjusted 40%), putting that much of the floor at risk—and therefore requiring careful management to prevent market losses from damaging the ability of the floor to cover expenses.

The Foundation for

Solving the Puzzle

There is a misapprehension that using balance sheet risk

management to allocate financial capital is somehow insurance product centric, puts

safety-first above all, or is just liability matching in a different costume.

It can be used to allocate any of those things, just as it can also be used to

allocate a total return portfolio, a dedicated floor with upside, a bucket

system, or a combination of upside portfolio, bond ladder, and insured products.

All of those things are about implementation, and are independent of the

mathematical determination of how much household FC should be managed as

upside, floor, longevity, and held for reserve.

Balance sheet analysis comes before implementation. It

replaces the narrow view of the investment portfolio and total-return allocation

theories as the central focus of retirement with a broader understanding of the

overall household financial situation and managing all the risks that can

affect the retirement plan, not just investment risk.

The household balance sheet, not portfolio theory, is the

foundation of personal financial management, anywhere in the lifecycle. A solid

understanding of the household balance sheet provides the basis for a

reasonable and practical way to solve the puzzle of how to best use household

resources to fund retirement or reach other goals.

This is a brief introduction to a subject with a deep body

of knowledge that is typically not part of an investment advisor’s agenda. For

more information, check the reading list at the

Retirement Income Industry Association website for links to additional

readings and sources.

--Michael Lonier, RMA®

Monday, November 10, 2014

Are Social Security Benefits a Bond?

Jack Bogle has suggested in the past that Social Security benefits are like a bond and should be treated as such in his “age in bonds’ allocation strategy. His reasoning is, I believe, that having that safe stream of income allows you to take more risk by buying more stocks with the rest of your investments, and it does.

Whether or not you should buy more stocks, of course, depends on your risk capacity, risk tolerance and current wealth and spending, and not simply on your age. Just because you can buy more stocks doesn't mean that you should. I also agree that a retirement income plan should consider all of a household’s assets, including Social Security benefits.

I draw a line, however, at including the present value of Social Security benefits into the bond portion of an upside portfolio to calculate my asset allocation. That’s why I recommended considering Social Security benefits as a component of the floor portfolio in Three Portfolios and calculating the asset allocation of the risky portfolio separately.

(There is a good discussion on this topic — there usually is — in the Bogleheads forum. You will notice that most posters, despite being members of a forum devoted to the philosophies of Jack Bogle, as am I, aren't really on-board with his position in this case.)

There are several ways in which Social Security benefits are not like a bond, and therein lies the problem.

First, we can't buy or sell Social Security benefits. If we include them in our asset allocation, we can't rebalance that allocation.

Second, for most American households, the present value of Social Security benefits is the largest component of the household's wealth, followed by home equity and then retirement savings. Treating the present value of Social Security as a bond would force most households to invest their entire savings in stocks and still not be able to achieve a reasonable asset allocation.

(The present value of Social Security benefits can be estimated by getting a quote for a life annuity from an insurance company with payouts equal to expected Social Security benefits. In today's interest rate environment, multiplying your expected annual benefits at retirement age by 20 will put you in the ballpark of their present value. For a more accurate valuation, I like Income Solutions at Vanguard.com for a quick online quote.)

Third, and perhaps most importantly, few retirees will value the present value of Social Security benefits as highly as they value an equal amount of stocks and actual bonds at the margin. They might (should) like the benefits better for a large portion of their wealth, but be unwilling to convert all of their stocks and bonds to illiquid Social Security benefits.

Retirees have expressed this preference by refusing to annuitize all of their retirement savings. It's a nearly identical scenario, given that Social Security benefits are an annuity. It stands to reason that they would be equally reluctant to back into an all-annuity position by risking the loss of much of their liquid portfolio.

Stocks and real bonds can be converted to cash to meet emergencies, to spend more in some years than others, or to take advantage of investment opportunities. If you need more money from Social Security benefits, all you can do is wait. Consequently, retirees with most of their wealth in the present value of Social Security benefits should be inclined to take less risk with their relatively small portfolio of stocks and bonds, certainly less risk than a 100%-stock portfolio would entail.

Social Security benefits reduce risk no matter how you treat them in an asset allocation because they reduce spending from a risky portfolio. The probability of a systematic withdrawals portfolio surviving decreases with more spending. Reduce spending from that risky portfolio by spending Social Security benefits, instead, and you can significantly extend the life of your savings.

In fact, reducing spending is usually a more effective way of reducing risk than is adding bonds to your portfolio. As William Bengen's chart below shows (focus on the 30-year line), unless you currently hold more than 70% stocks, adding more bonds doesn't change the SWR rate much. (If the sustainable withdrawal rate decreases, it is because SOR risk has increased, and vice versa, so a falling curve indicates more risk.) Adding bonds below a 30% stock allocation actually worsens risk.

Treating benefits as a bond in the asset allocation requires the purchase of more equities to obtain a desired asset allocation and thereby increases risk.

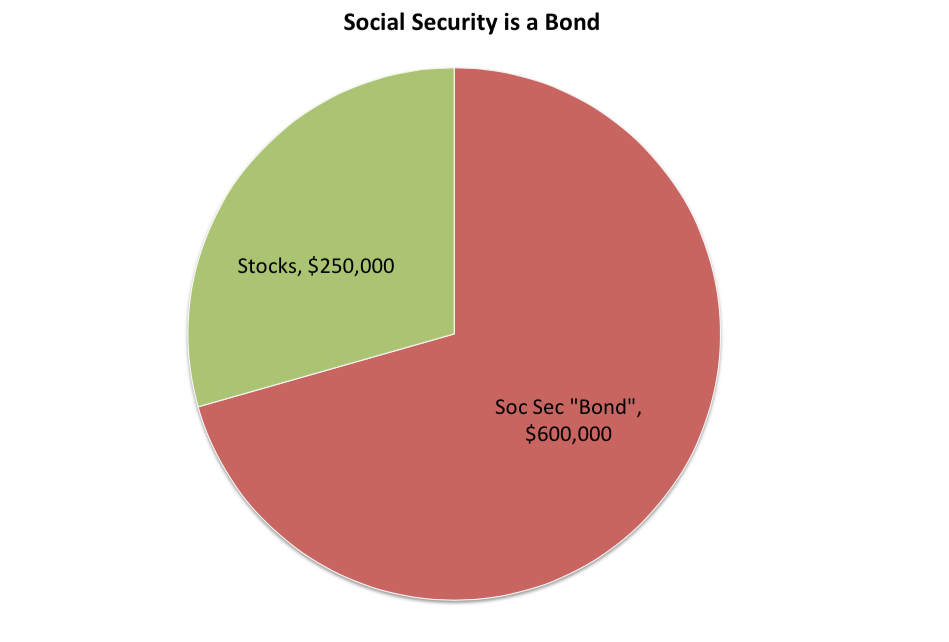

Here is an example of the two alternatives, considering the present value of Social Security benefits as a bond in the asset allocation as shown in the top chart below, and omitting them from that calculation in the bottom chart.

Assume a household has $250,000 saved in a 401(k). They expect $30,000 a year from Social Security benefits and can buy a similar life annuity today from an insurance company for $600,000. The household might consider their Social Security benefits, then, to be a bond worth $600,000. Let’s further assume that the household would prefer a 50% bond portfolio because they wouldn’t be comfortable with more than a 20% loss of their savings ($50,000) in a bear market crash.

The riskiest portfolio allocation this family can implement for their savings, when considering their benefits a bond, is obtained by investing all $250,000 in stocks. Doing so would still only create a 29% equity portfolio ($250,000 / $850,000), but a 100%-stock upside portfolio. They would have lost over 50% of their cash and bond value ($125,000) in the 2007-2009 market crash and 100% equities is well beyond what Bengen found to be optimal for systematic withdrawals.

Had they ignored Social Security benefits for asset allocation purposes, alternatively, they would hold $125,000 in stocks, $125,000 in bonds and would have lost about 20% of that, or $50,000, in 2007-2009.

If your are so fortunate that the present value of your Social Security benefits is a small portion of your household wealth, which is to say you are quite wealthy, treating Social Security benefits as a bond in the asset allocation will make little difference. But most American households aren't wealthy.

I recommend that you calculate your asset allocation both ways. If you’re comfortable with the equity allocation this forces on your upside portfolio, then consider Social Security benefits a bond for asset allocation purposes. If doing so would leave you with an unacceptably high equity allocation inside your upside portfolio, then consider the benefits part of your floor portfolio and manage the upside portfolio separately.

I don’t see an advantage to the Bogle suggestion. It increases risk by increasing your equity allocation. Benefits reduce SOR risk by decreasing spending from your risk portfolio no matter how you consider them in your asset allocation. The present value of your benefits can’t be rebalanced and doesn’t have the liquidity of stocks and real bonds. Total spending is decreased when you consider Social Security benefits a bond because the SWR component of income is reduced by the excessive equity allocation of the spending portfolio, from 4.4% to 3.6% of the upside portfolio in this example.

Placing the benefits in your floor portfolio and ignoring them when calculating your risky portfolio’s equity allocation, as I suggested in Three Portfolios, provides a lot more control of your savings portfolio and, in most cases, exposes you to less risk with more spending.

So, in this case I suggest you take the easy route. Consider your Social Security benefits a safe source of income and address your spending needs net of those benefits separately.

-----------------

P.S. The Yin and Yang of Retirement Income Philosophies, new from Wade Pfau's blog is great stuff!

Whether or not you should buy more stocks, of course, depends on your risk capacity, risk tolerance and current wealth and spending, and not simply on your age. Just because you can buy more stocks doesn't mean that you should. I also agree that a retirement income plan should consider all of a household’s assets, including Social Security benefits.

I draw a line, however, at including the present value of Social Security benefits into the bond portion of an upside portfolio to calculate my asset allocation. That’s why I recommended considering Social Security benefits as a component of the floor portfolio in Three Portfolios and calculating the asset allocation of the risky portfolio separately.

(There is a good discussion on this topic — there usually is — in the Bogleheads forum. You will notice that most posters, despite being members of a forum devoted to the philosophies of Jack Bogle, as am I, aren't really on-board with his position in this case.)

There are several ways in which Social Security benefits are not like a bond, and therein lies the problem.

First, we can't buy or sell Social Security benefits. If we include them in our asset allocation, we can't rebalance that allocation.

Second, for most American households, the present value of Social Security benefits is the largest component of the household's wealth, followed by home equity and then retirement savings. Treating the present value of Social Security as a bond would force most households to invest their entire savings in stocks and still not be able to achieve a reasonable asset allocation.

(The present value of Social Security benefits can be estimated by getting a quote for a life annuity from an insurance company with payouts equal to expected Social Security benefits. In today's interest rate environment, multiplying your expected annual benefits at retirement age by 20 will put you in the ballpark of their present value. For a more accurate valuation, I like Income Solutions at Vanguard.com for a quick online quote.)

Third, and perhaps most importantly, few retirees will value the present value of Social Security benefits as highly as they value an equal amount of stocks and actual bonds at the margin. They might (should) like the benefits better for a large portion of their wealth, but be unwilling to convert all of their stocks and bonds to illiquid Social Security benefits.

Retirees have expressed this preference by refusing to annuitize all of their retirement savings. It's a nearly identical scenario, given that Social Security benefits are an annuity. It stands to reason that they would be equally reluctant to back into an all-annuity position by risking the loss of much of their liquid portfolio.

Stocks and real bonds can be converted to cash to meet emergencies, to spend more in some years than others, or to take advantage of investment opportunities. If you need more money from Social Security benefits, all you can do is wait. Consequently, retirees with most of their wealth in the present value of Social Security benefits should be inclined to take less risk with their relatively small portfolio of stocks and bonds, certainly less risk than a 100%-stock portfolio would entail.

Social Security benefits reduce risk no matter how you treat them in an asset allocation because they reduce spending from a risky portfolio. The probability of a systematic withdrawals portfolio surviving decreases with more spending. Reduce spending from that risky portfolio by spending Social Security benefits, instead, and you can significantly extend the life of your savings.

In fact, reducing spending is usually a more effective way of reducing risk than is adding bonds to your portfolio. As William Bengen's chart below shows (focus on the 30-year line), unless you currently hold more than 70% stocks, adding more bonds doesn't change the SWR rate much. (If the sustainable withdrawal rate decreases, it is because SOR risk has increased, and vice versa, so a falling curve indicates more risk.) Adding bonds below a 30% stock allocation actually worsens risk.

Treating benefits as a bond in the asset allocation requires the purchase of more equities to obtain a desired asset allocation and thereby increases risk.

Here is an example of the two alternatives, considering the present value of Social Security benefits as a bond in the asset allocation as shown in the top chart below, and omitting them from that calculation in the bottom chart.

Assume a household has $250,000 saved in a 401(k). They expect $30,000 a year from Social Security benefits and can buy a similar life annuity today from an insurance company for $600,000. The household might consider their Social Security benefits, then, to be a bond worth $600,000. Let’s further assume that the household would prefer a 50% bond portfolio because they wouldn’t be comfortable with more than a 20% loss of their savings ($50,000) in a bear market crash.

The riskiest portfolio allocation this family can implement for their savings, when considering their benefits a bond, is obtained by investing all $250,000 in stocks. Doing so would still only create a 29% equity portfolio ($250,000 / $850,000), but a 100%-stock upside portfolio. They would have lost over 50% of their cash and bond value ($125,000) in the 2007-2009 market crash and 100% equities is well beyond what Bengen found to be optimal for systematic withdrawals.

Had they ignored Social Security benefits for asset allocation purposes, alternatively, they would hold $125,000 in stocks, $125,000 in bonds and would have lost about 20% of that, or $50,000, in 2007-2009.

How would income be affected in these two scenarios? In both scenarios, the retiree could spend $30,000 a year from Social Security benefits.

In the Social Security bond scenario of the upper chart, again according

to Bengen, the systematic withdrawal rate for a 100% equity portfolio

would be about 3.6% of $250,000, or $9,000. That would support total annual spending of just

$39,000 a year.

In the scenario without a "Social Security bond", represented by the bottom pie chart, he could spend a systematic amount from the risky portfolio of about 4.4%, according to Bengen, with a 50% equity allocation of the spending portfolio, or $11,000, for total spending of $41,000 annually.

I recommend that you calculate your asset allocation both ways. If you’re comfortable with the equity allocation this forces on your upside portfolio, then consider Social Security benefits a bond for asset allocation purposes. If doing so would leave you with an unacceptably high equity allocation inside your upside portfolio, then consider the benefits part of your floor portfolio and manage the upside portfolio separately.

I don’t see an advantage to the Bogle suggestion. It increases risk by increasing your equity allocation. Benefits reduce SOR risk by decreasing spending from your risk portfolio no matter how you consider them in your asset allocation. The present value of your benefits can’t be rebalanced and doesn’t have the liquidity of stocks and real bonds. Total spending is decreased when you consider Social Security benefits a bond because the SWR component of income is reduced by the excessive equity allocation of the spending portfolio, from 4.4% to 3.6% of the upside portfolio in this example.

Placing the benefits in your floor portfolio and ignoring them when calculating your risky portfolio’s equity allocation, as I suggested in Three Portfolios, provides a lot more control of your savings portfolio and, in most cases, exposes you to less risk with more spending.

So, in this case I suggest you take the easy route. Consider your Social Security benefits a safe source of income and address your spending needs net of those benefits separately.

-----------------

P.S. The Yin and Yang of Retirement Income Philosophies, new from Wade Pfau's blog is great stuff!

Wednesday, November 5, 2014

RIIA Webinar -- Sequence of Returns Risk

Powerpoint slides for the Retirement Income Industry Association webinar that I presented November 5, 2014 on Sequence of Returns Risk can be downloaded here. RIIA will soon post the video of the presentation and I will provide a link to it from this page as soon as it is available.

Whether you attended the webinar or viewed it later, please post any questions in the comments section below.

Following are responses to questions that were sent to RIIA.

Q: But the risk to a saver in the sense of IMPACT to portfolio is higher nearer retirement because the value of the portfolio is typically at highest point

Q: Aren't portfolios in accumulation less susceptible to the order of returns as long as you rebalance into relatively underperforming assets over time...and are passive as well?

Q: Talk about bond ladders of zeros as a strategy in retirement please

A: TIPS Bond Ladders are an attempt to build a better personal annuity in a safer way than SWR, which attempts it with stocks. Treasury ladders have no credit default risk, while annuities are subject to the financial strength of the insurance company. Annuities have no residual value after you and your spouse die (there are some protection features available at a cost), but your heirs can receive any unspent TIPS bonds left in the ladder. You can’t really build your own annuity either way, since annuities pool longevity risk. You can build a 30-year TIPS Bond ladder if you can afford it, but if you live 35 years, an annuity will still provide income.

A: It is considered in bond ladders if the bonds aren’t Treasuries. The U.S. government is prohibited by law from defaulting on a Treasury bond. I only recommend Treasury bonds for retirement ladders.

Q: How does this all relate to a risk-adjusted return approach to portfolio allocation? As you noted, different asset types have different returns (and even within bonds)?

A: The chart I showed from Bengen shows the effect of equity allocation on SOR Risk. It doesn’t matter how you arrive at a particular equity allocation. However you arrive at an equity allocation, it appears that you will increase SOR Risk with greater than about 70% equities.

A: Yes. Spending directly impacts SOR Risk and taxes are more spending.

A: Only these. Inflation isn’t a problem for the foreseeable future. And future market returns may not look like past returns. There are more good arguments that growth will be slower than there are that it will increase. I wouldn’t bet my standard of living that things will turn out in the future the way they have in the past.

A: My favorite question!

Q: Could one lower their sequence of returns risk by beginning retirement with a relatively low SWR level (say, 2.5%) and then slowly increasing the SWR up to the more traditional rate (about 4%) over the course of a few years at the beginning of retirement (say the first 5 years)?

A: Yes. Anything that lowers your spending from a risky portfolio lowers your SOR Risk. Some people can spend less early because they have a part-time job, for example.

Q: GREAT JOB - thanks Dirk I really like your blog!

A: We have a tie for best question!

A: Without commenting on reverse mortgages, because I have little exposure to them, what I do know is that they would behave much like an annuity, reduce spending from a risky portfolio, and thereby reduce sequence of returns risk.

Whether you attended the webinar or viewed it later, please post any questions in the comments section below.

Following are responses to questions that were sent to RIIA.

Q: But the risk to a saver in the sense of IMPACT to portfolio is higher nearer retirement because the value of the portfolio is typically at highest point

A: True. As I mentioned in the webinar, a typical retiree will make the largest

bets at the end of saving and the beginning of spending. That’s why it’s

important to lower your equity allocation during those times to place smaller

bets on stocks. Sorry if that wasn’t clear. I tried to circle both areas of the

graph with my cursor.

Q: Aren't portfolios in accumulation less susceptible to the order of returns as long as you rebalance into relatively underperforming assets over time...and are passive as well?

Good question! Rebalancing seems to help, at least based on

historical data, in both saving and spending stages. Using the RetireEarly Homepage model, rebalancing

improved a 91% failure rate to 95% with 4.7% spending in the past. But, most

SWR studies rebalance, including Bengen’s original work, so the spending rates

you see are probably based on rebalanced portfolios already. Not rebalancing would probably make sustainable spending rates

a little smaller.

Q: Talk about bond ladders of zeros as a strategy in retirement please

A: TIPS Bond Ladders are an attempt to build a better personal annuity in a safer way than SWR, which attempts it with stocks. Treasury ladders have no credit default risk, while annuities are subject to the financial strength of the insurance company. Annuities have no residual value after you and your spouse die (there are some protection features available at a cost), but your heirs can receive any unspent TIPS bonds left in the ladder. You can’t really build your own annuity either way, since annuities pool longevity risk. You can build a 30-year TIPS Bond ladder if you can afford it, but if you live 35 years, an annuity will still provide income.

If you search my blog at The

Retirement Café for TIPS Bond Ladders, you will find several posts with

more information (here, for example.). I plan to write on the topic again soon, so please check

back.

I would say that the major problem with TIPS Bond ladders today is

their high cost, given historically low interest rates (the same is true of

annuities). I’d recommend a 15-year rolling TIPS Bond ladder.

Q: Why is credit/default risk not considered in bond ladders? It

was mentioned home loans from the debtor side.

A: It is considered in bond ladders if the bonds aren’t Treasuries. The U.S. government is prohibited by law from defaulting on a Treasury bond. I only recommend Treasury bonds for retirement ladders.

Q: How does this all relate to a risk-adjusted return approach to portfolio allocation? As you noted, different asset types have different returns (and even within bonds)?

A: The chart I showed from Bengen shows the effect of equity allocation on SOR Risk. It doesn’t matter how you arrive at a particular equity allocation. However you arrive at an equity allocation, it appears that you will increase SOR Risk with greater than about 70% equities.

A: Yes. Spending directly impacts SOR Risk and taxes are more spending.

The impact of inflation on your portfolio depends on the assets

you hold. TIPS and Social Security benefits are adjusted for inflation, so

there is little impact. Stocks perform poorly when inflation is high, but their

returns typically make up for it over the long term. Payments from a pension

with no COLA adjustments would be worth less and less over time, requiring you

to spend more from your risky portfolio and increasing SOR Risk by increasing

spending.

Q: Any comment on Kitces analysis of how SOR risk and inflation

periods have played out in history?

A: Only these. Inflation isn’t a problem for the foreseeable future. And future market returns may not look like past returns. There are more good arguments that growth will be slower than there are that it will increase. I wouldn’t bet my standard of living that things will turn out in the future the way they have in the past.

Q: Great presentation!

Followed you right to the end.

A: My favorite question!

Q: It seems like sequence of returns risk is magnified in a

retirement where on uses a constant dollar spending approach (Bengen). Couldn't one solve for sequence of returns by

being more flexible with their spending, such as using a constant percentage

approach (theoretically never running out of money though spending could

potentially decline to a low number at some point)?

A: Yes. I wrote a series at The Retirement Café entitled

“Clarifying Sequence of Returns Risk” showing that a constant percentage

approach is safer. But as William Sharpe says, “Isn’t it self-evident that your

spending should depend on how much money you now have?”

I’ve been retired for 10 years and how much money I used to have when I first retired doesn’t

seem to matter to anyone.

Q: Could one lower their sequence of returns risk by beginning retirement with a relatively low SWR level (say, 2.5%) and then slowly increasing the SWR up to the more traditional rate (about 4%) over the course of a few years at the beginning of retirement (say the first 5 years)?

A: Yes. Anything that lowers your spending from a risky portfolio lowers your SOR Risk. Some people can spend less early because they have a part-time job, for example.

Q: GREAT JOB - thanks Dirk I really like your blog!

A: We have a tie for best question!

Q: Professor Stephen Sacks and I have done some work on mitigating

the effect of SOR (J. Fin'l Plng Feb 2012) using reverse mortgage credit

lines. Also, Professor John Salter and

others have done similar work. Could you

comment on that? Thanks, Barry H. Sacks

A: Without commenting on reverse mortgages, because I have little exposure to them, what I do know is that they would behave much like an annuity, reduce spending from a risky portfolio, and thereby reduce sequence of returns risk.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)