Wade Pfau recently posted a nice piece on how to build a TIPs ladder for retirement. A discussion ensued on the topic of whether one should build a ladder of individual TIPs bonds or instead buy a fund of TIPs bonds.

I'll chime in on the topic, but first let's talk about why a retiree should own bonds at all.

There are three basic alternatives for investing your savings after retirement. You can buy a life annuity from an insurance company that will pay you periodic amounts (let's assume monthly) for as long as you live. You will continue to receive these payments if you live to age 150, but you will stop receiving them when you die, even if that's next year.

The best thing about a life annuity is that you will never run out of money. The worst thing may be that you could end up with nothing left for your heirs.

(There are options you can buy to protect yourself against losing your investment if you don't live at least 10 years, to continue payments to a surviving spouse, and you can even purchase inflation protection, but let's not get into the weeds at this point.)

The second major alternative is to buy bonds. As William Sharpe and Jason Scott showed in "A 4% Rule -- At What Price?", you can invest in a ladder of TIPs bonds and, if interest rates follow long-term average returns of 2%, you can spend 4.46% of your initial portfolio value every year and your capital should last exactly 30 years. In other words, you can withdraw a constant $44.60 adjusted for inflation every year for 30 years for every $1,000 invested.

There are at least two major differences between these alternatives. First, the TIPs ladder will last exactly thirty years, at which time your account balance will be zero. The annuity pays for the remainder of your life, which could be significantly more or less than 30 years.

Second, you give your principal to the insurance company up front for an annuity, but you always own the bonds in your bond ladder. If you live less than 30 years, you can leave the surplus bonds to heirs. Depending on the options you choose, there may be nothing left of an annuity to bequeath.

Second, you give your principal to the insurance company up front for an annuity, but you always own the bonds in your bond ladder. If you live less than 30 years, you can leave the surplus bonds to heirs. Depending on the options you choose, there may be nothing left of an annuity to bequeath.

The third major alternative for your post-retirement investment dollars is a stock portfolio. You could invest in stocks and spend from the portfolio each year. Maybe you could pay your annual expenses and end up with a large portfolio to leave your heirs. Or maybe you will completely run out of money long before you die. There's a lot of upside potential with this approach, and a roughly equal downside.

A commenter on the Pfau thread suggested that he prefers investing in dividend-generating stocks, with a goal of spending dividends of around 4% and, unlike the annuity or TIPs ladder approach, being able to preserve his capital. Preserving capital is, in fact, one possible outcome. Going broke in old age is another. Stocks don't always go up.

Another commenter on the Pfau thread asked why you would invest in risky stocks and spend 4% a year when you could invest in a TIPs ladder and spend 4.5%. Part of the answer is that at the end of 30 years, the TIPs ladder is completely spent, principal and all. The value of the stock portfolio, on the other hand, could be enormous after 30 years, or it might not last 20 years.

The other part of the answer is that 4.5% is a pretty predictable spend rate for the TIPs ladder, while 4% for the stock portfolio is merely a guess.

Another commenter on the Pfau thread asked why you would invest in risky stocks and spend 4% a year when you could invest in a TIPs ladder and spend 4.5%. Part of the answer is that at the end of 30 years, the TIPs ladder is completely spent, principal and all. The value of the stock portfolio, on the other hand, could be enormous after 30 years, or it might not last 20 years.

The other part of the answer is that 4.5% is a pretty predictable spend rate for the TIPs ladder, while 4% for the stock portfolio is merely a guess.

Of course, you can bet some of your retirement on a combination of two or three of these alternatives, and that is probably the more common strategy.

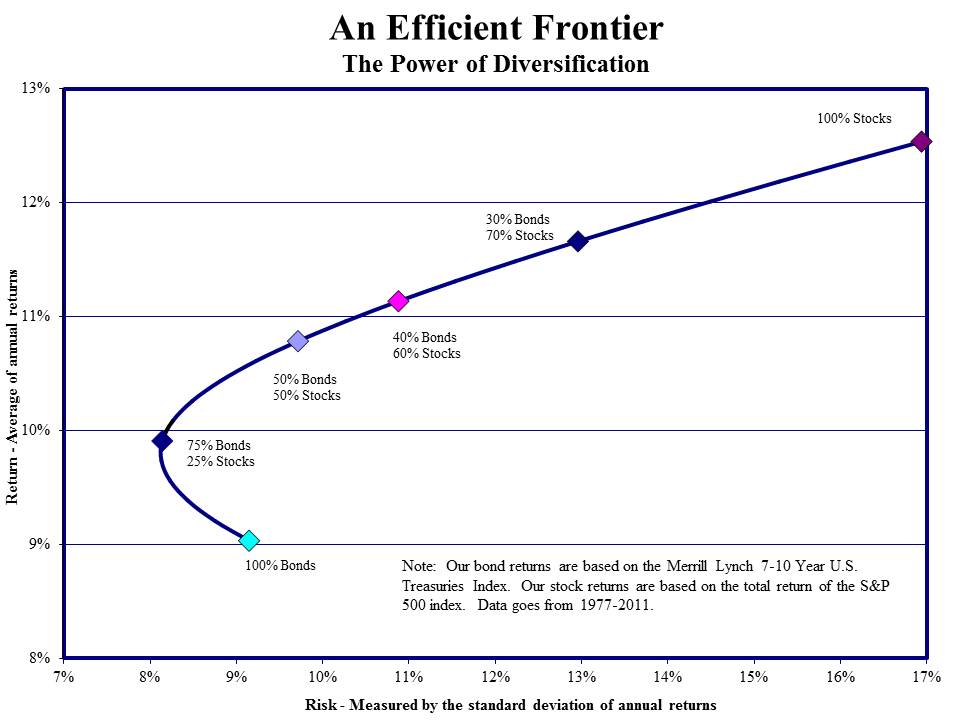

So, back to why a retiree should own bonds. If you decide to go the stock portfolio route, you should probably also own some bonds. As Modern Portfolio Theory predicts, bonds can decrease the risk of a portfolio a lot while lowering its return just a little. Deciding how much of your portfolio should be held in bonds at what age is still hotly debated.

|

| (from Young Research & Publishing) |

As an example, Index Fund Advisors calculates that the long term average return for a portfolio of 50% stocks and 50% bonds is 8.15% with a standard deviation (risk) of 11.42%. Lowering the stock allocation from 50% to 40% reduces the expected return to 7.39% (9.33% lower) but reduces the standard deviation to 9.28% (an 18.7% reduction of risk).

Another reason to own bonds is that they can provide a safe, predictable amount of future income. Let's say you predict that you will need $30,000 in 2019, five years from now, and you can find TIPs bonds in the market that mature in 2019 that currently offer a real yield-to-maturity of 2%. Let's simplify matters by assuming that the TIPs bond you find is a zero coupon bond (there aren't any, for some reason). If you invest $27,172 in such bonds, you can be pretty sure that the bond will be worth $30,000 in 2013 dollars when it matures in 2019.

Do that for the next 30 years (or any number of consecutive years) and you have a bond ladder. You also have a safe, predictable, inflation-protected income stream.

Why buy bonds, then? Because they improve your risk/reward profile if you decide to go the stocks route and they can provide safe, predictable, inflation-protected income if you decide to go with a TIPs ladder. Remember these two benefits, because which you desire will be a determinant of whether you should buy a fund or individual TIPs. More on that later.

Go the annuity route and you probably don't need bonds. In fact, a fixed annuity is a lot like a bond, issued by an insurance company, with a lifetime coupon and no remaining value when you die.

Unless you annuitize all your retirement savings, you're probably going to want to own some bonds to reduce your stock portfolio volatility, or to ensure income for living expenses for some future years.

Probably both.

Unless you annuitize all your retirement savings, you're probably going to want to own some bonds to reduce your stock portfolio volatility, or to ensure income for living expenses for some future years.

Probably both.

Wade's original question, though, was whether to build a TIPs ladder or to buy a fund, but we're not there, yet. Now that we've discussed why to buy bonds at all, the next question is "Why TIPs bonds"?